|

|

La Divina Commedia · Inferno

Canto XXXIV

Fourth Division of the Ninth Circle, the Judecca:

Traitors to their

Lords and Benefactors.

Lucifer, Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius.

The Chasm of Lethe. The Ascent.

«Vexilla regis prodeunt inferni

verso di noi; però dinanzi mira»,

disse 'l maestro mio, «se tu 'l discerni».

Come quando una grossa nebbia spira,

o quando l'emisperio nostro annotta,

par di lungi un molin che 'l vento gira,

veder mi parve un tal dificio allotta;

poi per lo vento mi ristrinsi retro

al duca mio, ché non lì era altra grotta.

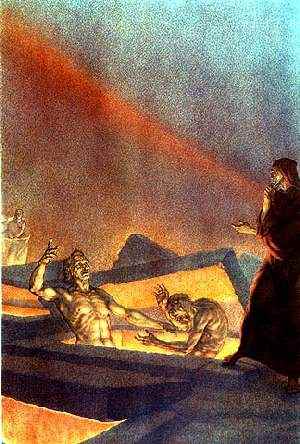

Già era, e con paura il metto in metro,

là dove l'ombre tutte eran coperte,

e trasparien come festuca in vetro.

Altre sono a giacere; altre stanno erte,

quella col capo e quella con le piante;

altra, com' arco, il volto a' piè rinverte.

Quando noi fummo fatti tanto avante,

ch'al mio maestro piacque di mostrarmi

la creatura ch'ebbe il bel sembiante,

d'innanzi mi si tolse e fé restarmi,

«Ecco Dite», dicendo, «ed ecco il loco

ove convien che di fortezza t'armi».

Com' io divenni allor gelato e fioco,

nol dimandar, lettor, ch'i' non lo scrivo,

però ch'ogne parlar sarebbe poco.

Io non mori' e non rimasi vivo;

pensa oggimai per te, s'hai fior d'ingegno,

qual io divenni, d'uno e d'altro privo.

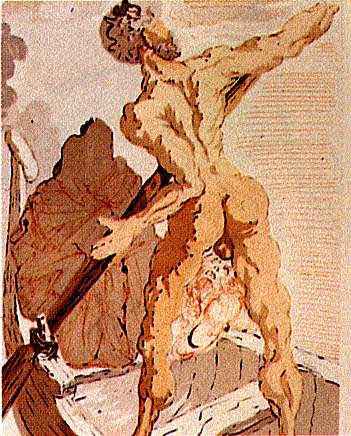

Lo 'mperador del doloroso regno

da mezzo 'l petto uscia fuor de la ghiaccia;

e più con un gigante io mi convegno,

che i giganti non fan con le sue braccia:

vedi oggimai quant' esser dee quel tutto

ch'a così fatta parte si confaccia.

S'el fu sì bel com' elli è ora brutto,

e contra 'l suo fattore alzò le ciglia,

ben dee da lui procedere ogne lutto.

Oh quanto parve a me gran maraviglia

quand' io vidi tre facce a la sua testa!

L'una dinanzi, e quella era vermiglia;

l'altr' eran due, che s'aggiugnieno a questa

sovresso 'l mezzo di ciascuna spalla,

e sé giugnieno al loco de la cresta:

e la destra parea tra bianca e gialla;

la sinistra a vedere era tal, quali

vegnon di là onde 'l Nilo s'avvalla.

Sotto ciascuna uscivan due grand' ali,

quanto si convenia a tanto uccello:

vele di mar non vid' io mai cotali.

Non avean penne, ma di vispistrello

era lor modo; e quelle svolazzava,

sì che tre venti si movean da ello:

quindi Cocito tutto s'aggelava.

Con sei occhi piangëa, e per tre menti

gocciava 'l pianto e sanguinosa bava.

Da ogne bocca dirompea co' denti

un peccatore, a guisa di maciulla,

sì che tre ne facea così dolenti.

A quel dinanzi il mordere era nulla

verso 'l graffiar, che talvolta la schiena

rimanea de la pelle tutta brulla.

«Quell' anima là sù c'ha maggior pena»,

disse 'l maestro, «è Giuda Scarïotto,

che 'l capo ha dentro e fuor le gambe mena.

De li altri due c'hanno il capo di sotto,

quel che pende dal nero ceffo è Bruto:

vedi come si storce, e non fa motto!;

e l'altro è Cassio, che par sì membruto.

Ma la notte risurge, e oramai

è da partir, ché tutto avem veduto».

Com' a lui piacque, il collo li avvinghiai;

ed el prese di tempo e loco poste,

e quando l'ali fuoro aperte assai,

appigliò sé a le vellute coste;

di vello in vello giù discese poscia

tra 'l folto pelo e le gelate croste.

Quando noi fummo là dove la coscia

si volge, a punto in sul grosso de l'anche,

lo duca, con fatica e con angoscia,

volse la testa ov' elli avea le zanche,

e aggrappossi al pel com' om che sale,

sì che 'n inferno i' credea tornar anche.

«Attienti ben, ché per cotali scale»,

disse 'l maestro, ansando com' uom lasso,

«conviensi dipartir da tanto male».

Poi uscì fuor per lo fóro d'un sasso

e puose me in su l'orlo a sedere;

appresso porse a me l'accorto passo.

Io levai li occhi e credetti vedere

Lucifero com' io l'avea lasciato,

e vidili le gambe in sù tenere;

e s'io divenni allora travagliato,

la gente grossa il pensi, che non vede

qual è quel punto ch'io avea passato.

«Lèvati sù», disse 'l maestro, «in piede:

la via è lunga e 'l cammino è malvagio,

e già il sole a mezza terza riede».

Non era camminata di palagio

là 'v' eravam, ma natural burella

ch'avea mal suolo e di lume disagio.

«Prima ch'io de l'abisso mi divella,

maestro mio», diss' io quando fui dritto,

«a trarmi d'erro un poco mi favella:

ov' è la ghiaccia? e questi com' è fitto

sì sottosopra? e come, in sì poc' ora,

da sera a mane ha fatto il sol tragitto?».

Ed elli a me: «Tu imagini ancora

d'esser di là dal centro, ov' io mi presi

al pel del vermo reo che 'l mondo fóra.

Di là fosti cotanto quant' io scesi;

quand' io mi volsi, tu passasti 'l punto

al qual si traggon d'ogne parte i pesi.

E se' or sotto l'emisperio giunto

ch'è contraposto a quel che la gran secca

coverchia, e sotto 'l cui colmo consunto

fu l'uom che nacque e visse sanza pecca;

tu haï i piedi in su picciola spera

che l'altra faccia fa de la Giudecca.

Qui è da man, quando di là è sera;

e questi, che ne fé scala col pelo,

fitto è ancora sì come prim' era.

Da questa parte cadde giù dal cielo;

e la terra, che pria di qua si sporse,

per paura di lui fé del mar velo,

e venne a l'emisperio nostro; e forse

per fuggir lui lasciò qui loco vòto

quella ch'appar di qua, e sù ricorse».

Luogo è là giù da Belzebù remoto

tanto quanto la tomba si distende,

che non per vista, ma per suono è noto

d'un ruscelletto che quivi discende

per la buca d'un sasso, ch'elli ha roso,

col corso ch'elli avvolge, e poco pende.

Lo duca e io per quel cammino ascoso

intrammo a ritornar nel chiaro mondo;

e sanza cura aver d'alcun riposo,

salimmo sù, el primo e io secondo,

tanto ch'i' vidi de le cose belle

che porta 'l ciel, per un pertugio tondo.

E quindi uscimmo a riveder le stelle.

|

La Divina Commedia · Inferno

Canto XXXIV

Fourth Division of the Ninth Circle, the Judecca:

Traitors to their

Lords and Benefactors.

Lucifer, Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius.

The Chasm of Lethe. The Ascent.

"Vexilla Regis prodeunt Inferni"

Towards us; therefore look in front of thee,"

My Master said, "if thou discernest him."

As, when there breathes a heavy fog, or when

Our hemisphere is darkening into night,

Appears far off a mill the wind is turning,

Methought that such a building then I saw;

And, for the wind, I drew myself behind

My Guide, because there was no other shelter.

Now was I, and with fear in verse I put it,

There where the shades were wholly covered up,

And glimmered through like unto straws in glass.

Some prone are lying, others stand erect,

This with the head, and that one with the soles;

Another, bow-like, face to feet inverts.

When in advance so far we had proceeded,

That it my Master pleased to show to me

The creature who once had the beauteous semblance,

He from before me moved and made me stop,

Saying: "Behold Dis, and behold the place

Where thou with fortitude must arm thyself."

How frozen I became and powerless then,

Ask it not, Reader, for I write it not,

Because all language would be insufficient.

I did not die, and I alive remained not;

Think for thyself now, hast thou aught of wit,

What I became, being of both deprived.

The Emperor of the kingdom dolorous

From his mid-breast forth issued from the ice;

And better with a giant I compare

Than do the giants with those arms of his;

Consider now how great must be that whole,

Which unto such a part conforms itself.

Were he as fair once, as he now is foul,

And lifted up his brow against his Maker,

Well may proceed from him all tribulation.

O, what a marvel it appeared to me,

When I beheld three faces on his head!

The one in front, and that vermilion was;

Two were the others, that were joined with this

Above the middle part of either shoulder,

And they were joined together at the crest;

And the right-hand one seemed 'twixt white and yellow;

The left was such to look upon as those

Who come from where the Nile falls valley-ward.

Underneath each came forth two mighty wings,

Such as befitting were so great a bird;

Sails of the sea I never saw so large.

No feathers had they, but as of a bat

Their fashion was; and he was waving them,

So that three winds proceeded forth therefrom.

Thereby Cocytus wholly was congealed.

With six eyes did he weep, and down three chins

Trickled the tear-drops and the bloody drivel.

At every mouth he with his teeth was crunching

A sinner, in the manner of a brake,

So that he three of them tormented thus.

To him in front the biting was as naught

Unto the clawing, for sometimes the spine

Utterly stripped of all the skin remained.

"That soul up there which has the greatest pain,"

The Master said, "is Judas Iscariot;

With head inside, he plies his legs without.

Of the two others, who head downward are,

The one who hangs from the black jowl is Brutus;

See how he writhes himself, and speaks no word.

And the other, who so stalwart seems, is Cassius.

But night is reascending, and 'tis time

That we depart, for we have seen the whole."

As seemed him good, I clasped him round the neck,

And he the vantage seized of time and place,

And when the wings were opened wide apart,

He laid fast hold upon the shaggy sides;

From fell to fell descended downward then

Between the thick hair and the frozen crust.

When we were come to where the thigh revolves

Exactly on the thickness of the haunch,

The Guide, with labour and with hard-drawn breath,

Turned round his head where he had had his legs,

And grappled to the hair, as one who mounts,

So that to Hell I thought we were returning.

"Keep fast thy hold, for by such stairs as these,"

The Master said, panting as one fatigued,

"Must we perforce depart from so much evil."

Then through the opening of a rock he issued,

And down upon the margin seated me;

Then tow'rds me he outstretched his wary step.

I lifted up mine eyes and thought to see

Lucifer in the same way I had left him;

And I beheld him upward hold his legs.

And if I then became disquieted,

Let stolid people think who do not see

What the point is beyond which I had passed.

"Rise up," the Master said, "upon thy feet;

The way is long, and difficult the road,

And now the sun to middle-tierce returns."

It was not any palace corridor

There where we were, but dungeon natural,

With floor uneven and unease of light.

"Ere from the abyss I tear myself away,

My Master," said I when I had arisen,

"To draw me from an error speak a little;

Where is the ice? and how is this one fixed

Thus upside down? and how in such short time

From eve to morn has the sun made his transit?"

And he to me: "Thou still imaginest

Thou art beyond the centre, where I grasped

The hair of the fell worm, who mines the world.

That side thou wast, so long as I descended;

When round I turned me, thou didst pass the point

To which things heavy draw from every side,

And now beneath the hemisphere art come

Opposite that which overhangs the vast

Dry-land, and 'neath whose cope was put to death

The Man who without sin was born and lived.

Thou hast thy feet upon the little sphere

Which makes the other face of the Judecca.

Here it is morn when it is evening there;

And he who with his hair a stairway made us

Still fixed remaineth as he was before.

Upon this side he fell down out of heaven;

And all the land, that whilom here emerged,

For fear of him made of the sea a veil,

And came to our hemisphere; and peradventure

To flee from him, what on this side appears

Left the place vacant here, and back recoiled."

A place there is below, from Beelzebub

As far receding as the tomb extends,

Which not by sight is known, but by the sound

Of a small rivulet, that there descendeth

Through chasm within the stone, which it has gnawed

With course that winds about and slightly falls.

The Guide and I into that hidden road

Now entered, to return to the bright world;

And without care of having any rest

We mounted up, he first and I the second,

Till I beheld through a round aperture

Some of the beauteous things that Heaven doth bear;

Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars.

(Translated by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

|

|---|